Chronic pain is complex, resulting from many inputs processed through the nervous system and the brain. As humans, we rely heavily on our vision to assess and navigate our environment and maintain balance.

Visual references are also one type of input the brain relies on to determine a potential threat to the organism. For example, have you ever found a bruise on your body that did not hurt until you noticed it there?

For those suffering from chronic neck pain, vision provides a great deal of feedback about cervical range of motion along with the mechano-receptors in the joints and soft tissue. The endpoint a person sees when turning his or her head and experiencing pain combines with a cluster of other information occurring at the same time to form the neuro-representation of the pain experience in the brain, or what Melzack (2001) calls a “neuro-signature.”

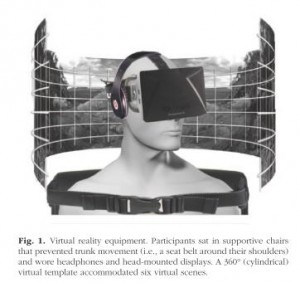

Harvie et al. (2015) investigated the role of visual feedback on neck pain. The researchers used a virtual-reality apparatus to alter the visual proprioceptive feedback that subjects received during cervical rotation. Subjects were seated with their torsos fixed to avoid contributing motion from the thoracic spine during cervical rotation. Twenty-four subjects with chronic neck pain were assessed for the onset of pain during cervical rotation to the left and right. They were asked to stop when they felt pain and to rate it on a scale of 0-10 at the point in the rotation where pain occurred. Each subject was then fitted with a virtual-reality headset that provided six different visual scenes for six trials. The image below is taken directly from the study by Harvie et al. (2015) and shows an illustration of the set up.

Researchers manipulated the virtual-reality scenes so that the visual cues did not match the actual cervical-rotation distance that subjects achieved on all trials. The virtual rotation provided by the headsets was either:

• 20% more than the actual rotation

• the same as the actual rotation

• 20% less than the actual rotation

This bogus visual feedback of plus or minus 20% made the subjects perceive that they were rotating their cervical spines 20% more or less than they actually were.

The results showed that when rotation was understated (subjects perceived their rotation was less than it actually was), pain-free range of motion increased by 6%. When rotation was overstated (subjects perceived their rotation was more than it actually was), pain-free range of motion decreased by 7%.

This study provides additional evidence to support the findings that pain is not generated solely from tissue damage. The bio-pyscho-social model acknowledges multiple inputs contributing to the pain experience.

Vision is one of many contributing inputs that the brain processes when assessing a threat to the body and therefore produces pain. The association of a specific neck range of motion identified visually, coupled with information from the motor system and proprioceptive system, creates a confirmed reference for past pain experiences. In other words, we’ve always had pain with this set of circumstances (neuro signature of matched proprioception, motor function, vision, vestibular), so we are supposed to have now. Hello pain.

It is plausible that visual input can also influence pain in other areas. For example, if a client has lower-back pain, forward flexion of the spine will bring her eyes closer to the floor, possibly presenting a painful or pain-free experience, depending on the client.

When designing a corrective program for clients where you believe the visual field is a factor, you could vary the visual field to minimize the visual association related to painful movements. Or you could keep the head still and create the motion you want from the bottom up-creating relative movement of the cervical spine in relation to the thoracic spine.

Interested in learning more about how we, at Function First and the Pain-Free Movement Specialists work with the chronic pain population? Enrollment is available only until April 29th here.

Melzack, R. 2001. Pain and the neuromatrix in the brain. Journal of Dental Education 65(12), 1378-82.

Harvie, D.S., et al. 2015. Bogus visual feedback alters onset of movement-evoked pain in people with neck pain. Psychological Science. doi:10.1177/0956797614563339.