Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is one of the most sensitive diagnostics currently available. It has frequently been the “last word” on pain, surgery and recommended limitations on activity. But should your client really never lunge or squat again because their doctor took an MRI and it showed some pathological condition?

Consider this review I did of a couple of studies on the matter. You may change the conversation you have with your clients once finished reading this.

Guermazi et. al. (2012) used magnetic resonance imaging to look at knees where radiographic imaging (x-rays) showed no osteoarthritic (OA) changes. OA is generally diagnosed through examination and x-ray. X-rays can identify bony changes to the joint but they cannot identify soft tissue pathologies. The purpose was to use the more sensitive MRI to detect structural lesions associated with OA and their relationship to age, sex and obesity.

710 subjects age 50 or older participated in the study (mean age 62.3 years). Out of the 710 subjects, 206 (29%) had painful knees.

Overall, 610 (89%) of the subjects showed some abnormality of the knee. Three most common findings of abnormalities in the knee were osteophytes, cartilage damage and bone marrow lesions. These abnormalities increased with age.

The study concluded that 91% of those who did have pain in their knee also had abnormal MRI’s, leaving 9% of those with painful knees having normal MRI’s. And 88% of those with no pain in their knees showed abnormalities in the MRI. The authors also noted that those with the highest amount of abnormalities in their MRI were those identified with mild pain and not those with moderate or severe pain (emphasis mine).

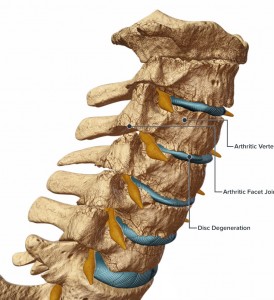

Another study in European Spine Journal (Kato et al. 2012) looked at MRI’s of the cervical spine of 1211 asymptomatic patients. The subjects were both men and women equally distributed between the ages of 20 years to 70 years. All of the subjects had both an MRI and neurological exam by a spinal surgeon.

Findings from the MRI of spinal cord compression, spinal cord signal changes and disc compression were noted. Increased signals on an MRI are associated with an abnormal state of the tissue such as scarring of inflammation.

For a disc bulge to be considered pathological it had to measure more than 1 millimeter from the vertebral body.

Of the 1211 asymptomatic subjects studied, 64 (5.3%) had spinal cord compression. High intensity signal changes were seen in 28 (2.3%) and disc bulging was seen in 1061 (87.6%) of subjects. Prevalence of these findings was significantly higher in people over 40 years of age.

If we consider the findings of both these studies, it is now clear that degenerative changes to the body are a normal part of aging and do not directly correlate with pain. Clients may experience stress or fear when learning of abnormalities in any joint or soft tissue following imaging studies done on them. Even if they are not in pain but have experienced pain in the past, the knowledge of degenerative changes are often communicated by medical professionals and perceived by individuals as the sole source of their pain. These studies clearly demonstrate that an individual can have many abnormal finding in the neck and knees and have no pain.

Clients who believe that the degenerative changes on their imaging will lead to pain may potentially act with self-limiting and guarded movements as well as an expectation of pain. This has the potential to decrease their functional capacity, increase anxiety about certain exercises or activities and view surgery as a necessary step to resolution.

Although I’ve suggested that your conversation should change with your clients, when you understand what these studies (and others) are telling us, we must remember that your client’s paradigm may not easily change. Their beliefs may be entrenched in an outdated pain/imaging relationship, especially if their doctor leads them to believe that the MRI finding is the final word.

They need proof. And ultimately that proof is movement confidence.

Guermazi, Ali August 2012. Prevalence of abnormalities in knees detected by MRI in adults without knee osteoarthritis: population based observational study (Framingham Osteoarthritis Study). BMJ, 345:e5339 doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5339).

Kato, Fumihiko et al. February 2012. Normal morphology, age-related changes and abnormal findings of the cervical spine. Part II: magnetic resonance imaging of over 1,200 asymptomatic subjects. Eur Spine J, DOI 10.1007/s00586-012-2176-4.