In 1971 I was just out of college and had moved to Eugene, Oregon, “running capital of the world,” to run. As an undergrad at the University of Hawaii I had won several state track titles, but had been significantly hampered by injuries, and I still wanted to see how good I could become.

It was Bill Bowerman’s last year as the University of Oregon coach, and the next year he would be the U.S. Olympic coach and founded Nike.

Consistent with my history I soon was injured in Oregon, this time with a heel spur/plantar fasciitis. Two Olympians, Steve Prefontaine (5K) and Mike Manley (steeplechase) showed me how to tape my foot which immediately got better, and surprisingly, my hip pointer (pain at the top of my pelvic bone) also went away. At the time I didn’t see the full significance of this, but it did start me thinking about how my foot, my foundation, affected the rest of my body.

I have come to recognize that most aches and pains are related to biomechanics. In this article I discuss what you can do about avoiding injuries, and especially about the foot’s role in avoiding them, the flip side of injury being efficient mechanics.

Two main ingredients make up mechanical health: good posture, and moving in a full connected way from the center of your body. A third, variety, helps you achieve the first two.

At a recent convention, the hot discussion was whether good foot posture, or good pelvic posture, was more important. That’s like asking, is it better to drink water or eat food? Good posture includes the whole body.

Nevertheless, I focus on footbeds/orthotics that address the foot’s posture, a “necessary and not sufficient” part of the puzzle, and leave the rest to people like Anthony.

The foot is your base of support, and in order to be balanced, the foot must be balanced. Imagine building a house on an unstable foundation.

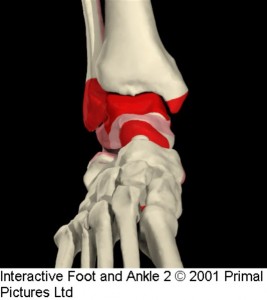

Although the foot is of particular importance, it is also uniquely difficult to balance because many of the foot’s bones are horizontal. While you can stack/nicely balance/ the bones in the rest of the body on top of one another, you cannot do that with the feet. In order to maintain their arch shape, the bones must be tightly held together, or the foot will collapse.

There are several soft tissue structures, namely the muscles, fascia and ligaments, which might do this.

Muscles can usually hold the arch up for a short time when you’re standing still and the forces are small. For example, if you weigh 100 pounds, the force on each foot is 50 pounds. It gets tougher when you walk however, when forces increase to 120 pounds, and extraordinarily more difficult when you run and the forces are 350 pounds. The bottom line is that muscles are not up to the task of providing good foot posture when you either stand for a longer period of time, or run. Indeed, muscles are designed to control and cause motion, and not be so involved in posture. If they do become too involved in posture, they become tight and sore.

Among the more common muscles that become tight from holding up the arch are the two hip flexors (Psoas major, Iliacus) and the Piriformis. Although they are external rotators, with the foot on the ground they lift up the arch. Tight hip flexors are associated with low back pain, and a tight Piriformis is associated with sciatic pain.

Fascia and ligaments are designed for postural support. It is their job to hold the arch up.

Fascia has the mechanical characteristic of being “plastic,” meaning that it adapts over time to what you ask it to do. Fascia is everywhere (the gristle in meat), and although it can support you in good posture, it often gets stuck supporting you in a hunched-over posture, making standing up straight more difficult. Typically it takes several months to change the length of fascia so that one day you might say “wow, standing up straight is not so difficult.”

Ligaments hold bones together, allowing movement while supporting structure. Their job is to limit joint distention and they become injured if stretched beyond a narrow range. Unlike muscles which actively contract, ligaments merely react to stretch, returning to their original position.

Because of their poor blood supply, ligaments are difficult to heal, which is why when you hurt your ankle, you often hope you break a bone, rather than stretch a ligament. Bones heal, often becoming stronger than they were originally, whereas stretched ligaments often remain longer, leaving you with a less stable joint.

When slowly stretched, as occurs over time, ligaments also become longer. When foot ligaments are longer, arches are flatter and your foundation is less aligned.

You might have inherited longer ligaments, or over time you might have lengthened your ligaments by exposing your foot to flat, hard surfaces. Since the foot adapts to the surface upon which you place it, by walking or running barefoot (or in minimalist shoes with no support), on a flat hard surface, you are asking your foot to become flatter. Our feet are not designed to function on these man-made surfaces, rather they are designed for randomly challenging, softer, supportive surfaces like pine needle covered forest paths strewn with rocks and roots; these surfaces keep your feet healthy.

The exception is if you have inherited longer ligaments and a flatter foot, in which case even the best environment won’t keep you healthy.

The consequence of a flatter foot, one that has poor posture, is the greater likelihood of many injuries, including injuries to the foot itself such as bunions, neuromas, plantar fasciitis and heel spurs, as well as to the Achilles, calf, shin, knee, groin, hip and low back. The ubiquitous plantar fasciitis, for example, is associated with excessive pulling on the plantar fascia (when the foot flattens, it also lengthens). There are many reasons behind this, including a tight calf and a rotated pelvis, but usually the primary risk factor is longer ligaments.

In that case it becomes necessary to complement the ligaments with a footbed that holds up the arch, creating good foot posture, which allows the muscles to do what they are designed to do, which is to move your body. How important the footbed is will depend on how misaligned you are without it. The longer your ligaments, the more misaligned you are, and the more time you want to spend being supported by a footbed.

Of course it is also important to deal with the other risk factors such as the problematic calf and pelvis; however that is not so much my business, nor is it the subject of this article.

I was also asked to comment on minimalist shoes, such as the Vibram five finger shoe, since they are somewhat the rage these days.

Under no circumstances that I can think of, will your feet be healthy if you walk or run barefoot for any period of time on man-made hard, flat surfaces. This includes minimalist shoes, which allow you to function as if you were barefoot.

I agree that shoes have become too cushioned and insulate us from our environment. Nevertheless, some of us tried the experiment of minimalist shoes back in the late ‘60s, when we used to run in black canvas Keds with a minimalist crepe rubber sole. Our feet lost some of their arch and spring, and we are suffering from that abuse today.

Of course, at the time we had young bodies, didn’t know any better, and loved our Keds. But I also remember my excitement in the early ’70s when I wore my first cushioned shoe, a Tiger (now Asics) Cortez, designed to compensate for the hard roads. Intuitively I sensed that the hardness of roads was part of the problem.

You will be able to run successfully in a minimalist shoe if you stick to softer, supportive, randomly changing surfaces, and if you have inherited sufficiently strong ligaments to maintain good foot posture. Otherwise, you’re asking for trouble.

I am also occasionally asked if footbeds make your muscles lazy. After reading this, you will realize the answer is no. Footbeds complement ligaments to achieve good posture. They don’t do the work of muscles. On the contrary, good foot posture allows the muscles to work in a more balanced, efficient way.

Doug Stewart, Ph.D. (biomechanics), went to college on a track scholarship, often trying to run 100 miles a week, and often getting injured. His injuries and a desire to be more efficient motivated him to address his mechanics, which as it turns out are human mechanics, and common to most of us☺. He makes footbeds, and can be reached for comments by emailing Dougstewart2@cox.net.